Revolutionary Gene Therapy Offers New Hope for Sickle Cell Disease Patients

- Uncategorized

- No Comment

- 99

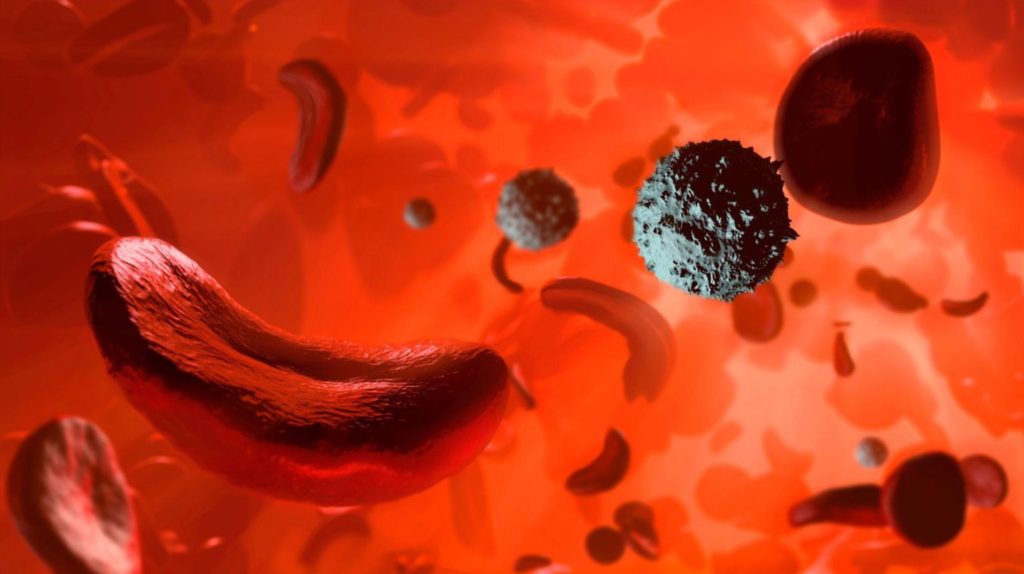

New findings from a clinical trial, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggest that stem cell gene therapy could be a potential curative treatment for sickle cell disease (SCD), a painful, inherited blood disorder.

This research adds to the growing evidence that supports gene therapy as a viable treatment option for SCD, a condition that predominantly affects people of color.

About 100,000 Americans have sickle cell disease, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The condition, which can cause a lifetime of pain, health complications, and expenses, affects one in 365 Black babies born in the U.S. and one in 16,300 Hispanic babies.

Advancements in Treatment Options

Until recently, the only treatment options have been intensive bone marrow transplants from siblings or matched donors. But other curative therapies are now on the horizon. The University of Chicago Medicine Comer Children’s Hospital was one of three sites to enroll patients in the clinical trial, which tested a stem cell gene therapy to treat sickle cell disease.

As part of the trial, researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 to edit specific genes in stem cells — the building blocks of blood cells — taken from each patient. The edits increased the cells’ production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), a protein that can replace unhealthy, sickled hemoglobin in the blood and protect against the complications of sickle cell disease. The patients then received their own edited cells as therapeutic infusions.

The therapy was the second for this disease to use CRISPR-Cas9 technology and the first to target a new genetic area and use cryopreserved stem cells with the hope of increasing access to such a treatment. Other gene therapy studies for SCD have used lentiviruses — a type of virus often modified and used for gene editing which remain in the cell long-term. No foreign material remains in stem cells edited with CRISPR-Cas9.

Clinical Trial Results and Patient Experiences

Trial participants who received the CRISPR-edited stem cells reported a decrease in vaso-occlusive events, a painful phenomenon that occurs when sickled red blood cells accumulate and cause a blockage.

“The biggest take-home message is that there are now more potentially curative therapies for sickle cell disease than ever before that lie outside of using someone else’s stem cells, which can bring a host of other complications,” said James LaBelle, MD, Ph.D., director of the Pediatric Stem Cell and Cellular Therapy Program at UChicago Medicine and Comer Children’s Hospital and senior author of the study. “Especially in the last 10 years, we’ve learned about what to do and what not to do when treating these patients. There’s been a great deal of effort towards offering patients different types of transplants with decreased toxicities, and now gene therapy rounds out the set of available treatments, so every patient with sickle cell disease can get some sort of curative therapy if needed. At UChicago Medicine, we’ve built infrastructure to support new approaches to sickle cell disease treatment and to bring additional gene therapies for other diseases.”

Future of Gene Therapy

As the scientific community continues to refine and expand the applications of gene therapy, the potential for curative treatments for diseases like sickle cell disease is becoming more of a transformative reality. The journey is ongoing, with the need for long-term follow-up and further research, but this study provides an encouraging glimpse into a future of effective genetic interventions.

In the larger context of therapeutic development, LaBelle stressed the importance of the study’s contribution to the growing body of evidence supporting the viability of gene therapy as a treatment for sickle cell disease. Two other gene therapies for the disease are awaiting FDA approval this year.

“The data from this trial supports bringing on similar gene therapies for sickle cell disease and for other bone marrow-derived diseases. If we didn’t have this data, those wouldn’t move forward,” he said.

By UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICAL CENTER